I voted for George W. Bush back in 2000.

My second grade class, for whatever reason, held a mock vote for that election. I can’t remember why I chose Bush – I don’t know if I knew anything about either him or Gore at that age. Perhaps I caught enough of the morning news before school to see how boring Al Gore was – you know, the important stuff. But the choice was more than likely entirely random.

There was something satisfying about his win – again, not because I was invested in what he stood for, or even understood what a president really did, but because it was my team. I didn’t see his verbal flubs, hear about any hanging chads – it was nothing but a popularity contest.

It’s easy to treat elections like a game when you don’t know enough to know it affects you. George H. Bush won – I won.

Author: foolfantastic

Review: Alita: Battle Angel (2019)

Alita: Battle Angel is a tale of an abandoned cyborg returned to life without her memories, finding herself in a ruined world beneath a floating city. It’s got all the features of a major studio blockbuster – big action sequences, a vibrant future noir world, an obligatory romance.

After months of staring this trailer down, I feel like I have to look it in the eye. It’s the most jarring detail, something painfully discomforting to look at. But where it turned me away from the film in the trailers, it works in the full context – it’s an intentional invocation of the uncanny valley, immediately marking Alita as out of place.

Alita: Battle Angel comes off as a film not certain of what it wants to be – it’s everything and nothing at once. Throughout the opening act, it sets itself up as if it’s going to be this classic dystopian tale with deep lore – and it really wants us to learn this lore, as the entire opening feels like nothing but exposition. But this doesn’t go anywhere – the dialogue is largely amateur, the elements of the world stale. There’s no attempt at any meaningful philosophical pondering, so why waste our time acting like there’s some grander concept at play?

Tacked onto this is a familiar love story, a young woman new to the world falling for the first young man who introduces her to it. There’s no meaningful chemistry between the two, but despite this failure, the film at least uses these moments to explore Alita as a character outside of the initial wonder and the later warrior.

After wasting our time with themes it doesn’t actually want to explore, Alita picks up the pace during the action sequences. This film is really dumb, and it’s at its best whenever it embraces that fact. It’s brutally violent and visually chaotic – that is what Rodriguez knows how to do. It’s a shame so many action directors feel a need to justify these battles – this film could have trimmed quite a bit of fat and been a much more engaging experience if it just dropped some of the political intrigue.

The one redeeming element of the narrative is Alita herself – this is a character who finds her own story, has passion and energy. These elements aren’t limited to her seeking out fights – her curiosity seems genuine, and her evolution as she begins to understand the world is largely successful. She’s alien in the right ways, making extreme gestures that are believably not as extreme from her cyborg perspective. All of this adds up to an ideal action protagonist, someone who carries the plot instead of being pushed along.

The worst part about this movie is that it ends – specifically, that it ends way before it actually ends. This is apparently going to be a story in multiple parts, as the conflict the movie keeps building toward doesn’t actually happen within the film. I felt blindsided by the credit roll – was their goal to leave the audience as immediately underwhelmed as possible? The film doesn’t do enough to leave me wanting to dive back into the narrative of this world – I just wanted a cool closing action sequence.

But the fact I wanted that means there’s some success – this is a movie that got better as it went on, to the point I must have been invested by the end. Between the lead character and the visual design, a sequel could turn out a lot better since it gets to skip over the set-up.

All in all, Alita: Battle Angel perfectly encapsulates the styles of both Rodriguez and James Cameron. There’s chaotic violence, a bold new world…and a consistently fumbled plot. If you can tolerate the sometimes maddening narrative, you’ll be rewarded with some truly fun action sequences.

3 Stars Out of 5

Review: Fyre (2019)

The failure of the Fyre Festival was one of those spectacular social media events, a cavalcade of schadenfreude as we collectively laughed as rich kids overreacted to a bad vacation. It was symbolic of issues within social media, an event carried entirely by hype and no outside oversight, sold through ‘influencers,’ with no one questioning who was running it and if they had ever done something similar before. Fyre dives into the background details, pinpointing the people involved and why it went wrong.

Being a documentary about recent events that are still tangled in legal issues and interviewing people who may or may not be culpable, Fyre is a film that needs to be met with heavy scrutiny – who is making this and what are they trying to say? If you went purely off this documentary as presented, everything seems to fall on CEO Billy McFarland, that rich white frat bro-type seemingly designed to be hated. He obviously is a central negative force – but an event this big has several people involved, and no one seemed to do anything meaningful to prevent the disaster from being fully realized. There was no excuse to allow people to actually arrive at the festival grounds.

What Fyre fails to meaningfully establish is that this was a scam created by rich people targeting rich people. The documentary casually introduces attendees, and they are never questioned. Who are these people that are willing to drop thousands of dollars on a festival without first making sure it was the real thing – especially one occurring in 2017 with Blink-182 as a headliner? These aren’t sympathetic figures, but Fyre is happy to drop successful venture capitalists in front of us and act like they’re everyday victims.

As long as you go in with a critical mind, Fyre does a pretty good job establishing what allowed this to happen – even if some people might be covering their own tails, there are solid elements being discussed, like how they managed such expert marketing and the struggles of attempting to put together a big event in such a short time. There were promises of something that had never been done before, with no one thinking to ask why it hadn’t been done before. This was a concept being sold as a finished product. There’s quite a bit of fun in seeing people who can usually buy their way out of every problem running into something that no amount of money can fix.

The film is at its strongest when it exposes the actual victims at the heart of the matter – as in people who were actually harmed by the festival. Interviews with the locals who did the actual ground work are depressing, people promised something meaningful for their community and then abandoned without pay. This would be a stronger documentary if they gave this subject more time – but Fyre seems to want to run off the more absurd elements.

The Fyre Festival is certainly an event worthy of a cinematic exploration, but this film is coming at a time where it allows certain people to save face – it’s hard to view it as a meaningful statement until the dust settles. It’s certainly a fun subject matter presented fashionably, but the film itself is teaching us not to trust presentations simply because they have a slick presentation. A fuller truth will be revealed in time – but this is a fair summary as we have it today.

3 Stars Out of 5

A Shortness of Breath

I was introduced to Godard in one of my first film classes. We watched Breathless, and it appeared most of my fellow students hated it.

For me, it was like the final piece of a puzzle. I got narrative, I got atmosphere, I was at least aware of the more technical aspects of cinema, but Breathless operated like an immediate lesson on editing. Of course all films have editing – well, almost all – but it tends to be a subtle form. The less you notice the better seems to be the common wisdom. Breathless tosses that aside, taking a Brechtian approach. If every cut is noticed, we are reminded again and again this is only a movie.

Where Eraserhead was like a chance encounter with a babbling Ancient One, Breathless is that jerk who explains every magic trick before it’s finished. Godard wants us to be aware how easily manipulated we are, to be aware how violent a simple cut can be.

It’s that moment at the beginning, where Michel shoots a cop and flees – but we never see the shooting, only a quick series of shots that suggest a shooting. Everything – well, almost everything – in fictional cinema is a construction, several stray shots connected to form a bigger whole.

I don’t believe Godard is a cynic to make such a film – quite the opposite, in fact. I can’t imagine anyone having more fun while actually making a movie. His love of cinema seems apparent in how he works in the medium. He doesn’t want to eradicate the illusion as much as he wants an informed audience – a more knowledgeable audience allows an artist to do more with their work.

There are certain people who seem to expect critics to be able to just turn off their judgment and take a movie in – as if everything we’ve learned through the thousands of movies we have watched can just be put aside for a few hours. People seem to think critics don’t have fun while watching movies – but the truth is that our idea of fun has changed with experience. So many traditionally ‘fun’ films rely on simple imagery, things that start to lose meaning once you’ve seen several films do the exact same thing. We don’t watch art films simply because they’re more ‘valuable’ or what-not; for someone who has viewed that many movies, it’s the more technical aspects that become fun. A truly great director offers a certain style that can’t be found elsewhere.

And because I think this needs emphasis – art films are fun. Critics wouldn’t be so enamored if they were bored. The opposite is also true – these big Hollywood productions become boring when you sit through enough of them. It’s not that we can’t have fun, as much as certain studios tend to cut corners and offer nothing new beyond some shiny visual effects. What’s enjoyable about an old experience with purely surface-level modifications?

We’re not some alien creatures, judging films with inexplicable criteria. In all honesty, I think there’s a certain point where the simple act of watching a movie should become a fun process. The idea of being ‘bored’ by a movie seems a foreign concept these days. And when you reach the point where the simple act of watching a film is fun, you have to develop criteria that looks beyond enjoyment – otherwise, every movie carries the same value.

To create art is a skill – what is often overlooked is that the act of consuming art likewise requires skill. No one is born with an understanding of cinema, or books, or music. Everything we see in this world was at some point learned. Never accept the easy answer – it might make things simple, but in the world of art, you’re missing so much because of it.

Like everything else in life, the effort you put into understanding film determines how much you can get out of it.

Slip Inside This House

Of all films, I think the one I’ve watched most is this semi-obscure horror comedy named Hausu, a Japanese production from the late 1970s.

Part of the appeal is how inexplicable it feels – it seems to go against everything I know about cinema. Eraserhead pushed the envelope, but Hausu tossed everything aside. It’s simplistic and gaudy, yet there’s this base appeal. I don’t believe in guilty pleasures – there had to be something that mad it work, even if I lacked the words.

I had rented it from Netflix just a month before heading off to college and was mesmerized – one of the first things I did after getting to college was meet up with a couple friends I made over the summer through Facebook, and we watched Hausu in the basement of Allen Hall.

It’s the perfect midnight movie – so colorful and bonkers to appeal to the so-bad-its-good aesthetic, but carrying enough technical weight to actually impress those paying close enough attention. What is it saying? Does it mean anything? It seems indecipherable, a work of pure viscera – but nothing great is that simple. A subtle meaning reveals itself with repeated viewings, much like Mulholland Drive – beneath its excess is commentary on the expectations of young women in Japanese society.

I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the film people most associate me with – it became a habit to show any new friend this film eventually. I’m infected and this is my virus – something this unique yet so under-watched needed to be spread.

We got in a fight about this movie several months back – you know I hold myself up as some sort of critic, and me saying it was a movie that defied explanation wasn’t enough. You were right – it was an empty answer. I wanted a film I could just enjoy without thinking – but there had to be something. No other film got that pass, so why this one?

The next night, I sat down and wrote everything I loved about the film. The connections became clear; the spectacle of Georges Melies, the conceptual treatment of concepts as found in early Soviet cinema, all mixed with contemporary psychedelia, feminism, and the baffling nature of Japanese advertising – Hausu speaks in several familiar languages, but it’s hard to make the jump from A Trip to the Moon to the late 70s without anything in-between. It’s as if director Obayashi imagined a world where we stuck to Melies’ fantastical sets and conspicuous editing tricks, where we decided to eschew realism entirely. It’s odd among films of the 1970s, but Hausu makes a surprising amount of sense in the context of early cinema.

In the end, while every film has its own method of communication, they are still limited by the overarching language of cinema. Every film, no matter how esoteric, has another film, another movement it can be connected to. No art exists in a vacuum – but a film like Hausu, one that takes so much effort to figure out how it fits, something that can trick us into believing someone made something wholly original over 70 years into the medium? They’re treasures that deserve to be cherished.

You’ve Got Your Good Things

Eraserhead was on Netflix and I decided to just turn it on one evening; I knew nothing of the film beyond faint whisperings of its oddness. Most likely, this lack of information is what made it such an effective experience.

Up until that point, most films I had encountered were traditional narratives. They had beginnings and ends, and most of the things between had a logical flow. And that’s how I thought films were supposed to be made – a visual method of telling a story.

Eraserhead worked its way beneath my skin. The opening was inexplicable, and its faint suggestion of plot as we start to follow Henry Spencer quickly unravels. It was more a waking nightmare than a traditional story.

I remember having to pause the film after a certain point – I had been watching with no lights on, my lack of expectations leaving me vulnerable. Where Spirited Away had left me breathless with its beauty, Eraserhead wrapped its hands around my throat. Few films have left me looking for an exit, and unlike the Elephants or Pink Flamingos of the world, I’m not sure how to explain why. There was no explanation for what was happening on screen, but I knew it didn’t feel good.

By leaving me so paralyzed with no easy explanation, one thing became clear – the art of cinema was never about plot. Individual films could be, but it was never a necessity. There was some other force there, something all films carried – I soon started to call it atmosphere. Films consist of hundreds of little pieces coming together for an emotional experience – stories just make those emotions easier to comprehend. I never had to consider this idea until coming in contact with a film that stripped everything digestible away.

The unfortunate part of our education system is it teaches us to appreciate art in a certain way – we are mainly taught through literature, and largely tested through simple memorization. Especially with how popular literary adaptations are, I think we’re subtly taught to read movies in the same way we read books – but by doing so, we ignore the technical and stylistic prose. Just like a good novel has expertly-chosen language, movies have angles and cuts. But so much gets overlooked for the elements that are easier, that I think everyone needs some sort of Eraserhead to wake them up to the truth.

So you can go ahead and be happy with the easy way out – to believe that all these artistic choices are nothing more than a stepping stone to tell stories. You’ve got a good thing there, to believe that the most important merit of art is whether it’s easily digestible, the same familiar stew you have been fed since grade school without question.

But lurking out there somewhere is an Eldritch work, something that will open your eyes to ideas that had gone unseen but can never be unseen again. Find it, embrace it, for every work you’ve loved before will have new meaning. You’ll learn that every frame, every cut is pulsing with life – or maybe they aren’t, and maybe those old favorites won’t be favorites much longer.

After all, it doesn’t take a hundred people to come together to simply tell a story.

The Spiriting Away of Topher and Chris

One of the first things we did after Mom introduced us was watch Jurassic Park together. I’m not sure why you chose this particular movie, you just like watching movies. The walls of your house are lined with posters, and you attend so-called ‘classes’ at the local art theater any week you can.

Until you entered my life, movies were this minor thing for me – I liked cartoons, but even then, I was happy enough to turn on Cartoon Network. My attention span was short and movies felt so long.

One day you introduced me to IMDB, and I decided to check out the top 250 list. I hadn’t heard of most of the movies, and I mainly sought out the animated films. I had seen most, besides a few from Japan. The one that stood out was Spirited Away – I remembered seeing it at the video store, and I was surprised to see it all the way in the top 50. It seemed like something worth checking out.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of that first watch – it felt like nothing was going to be the same again. Truthfully, several films might have triggered that revelation, but Spirited Away got there first.

There’s that sequence where Chihiro takes the train, and she looks ahead as her face is reflected in the window. It’s this quiet moment that says so much – of growing up in a scary new world. The entire film carries this air of joyous melancholy – the innocence of childhood shed and replaced by the confidence of a knowing maturity.

I sat in awe at the closing shot – Chihiro staring longingly at the entrance to that other world, both haunted and vitalized by her experience. So much can be said in a glance. It moved me almost to tears – for the first time, it felt like I had found something truly beautiful in this world.

When we returned the video to the store, I immediately picked up Fantasia and 2001: A Space Odyssey. I had something to drive me – if Spirited Away could make me feel so alive, there had to be others.

My whole life, I’ve been chasing the high of that first time. Very few works have touched me as much – the pieces falling into place the second time through Mulholland Drive, the two women’s faces spliced together near the end of Persona, that final question and responding scream as the third season of Twin Peaks closed out – and they all spoke more to horror than love. But I don’t need that gentle beauty Spirited Away blanketed me in – cinema itself has left me in awe.

I’m so grateful you’ve been a part of my life. Whether or not it was your goal, you helped me find my driving force. I spent my childhood chasing after this idea of a father figure, and you gave me more than I had imagined possible. Even though my goals sometimes feel impossible, you’ve always encouraged me to chase them. I always seem to credit finding Spirited Away as my entry point into the art of cinema – but really, it was you.

I just hope someday I have the strength to say these things to you directly. That you helped shape me into the person I am today, that I’m thankful I have you. I love you like I imagine a child loves their father – because that’s what you are to me.

Sleeps Tonight

One of your biggest regrets of my childhood was teaching me how to rewind.

I was a child of the Disney Renaissance, and The Lion King had taken up a permanent residence on our home TV. There are few memories from those early years, for our capacity to remember forms a bit later in life, but my first viewing several years later was like finding a text already coursing through my bloodstream.

It’s funny, how much you associated me with that film. You mentioned it a lot as I grew up, perhaps one of the few solid memories you have of me as a child in the outside world before being hauled off to prison. This gentle teasing, of something I would have never known without your little reminders – it brought a strange sense of warmth, a bright spot in a childhood marred by your actions.

The Lion King has been my eternal film, one so ingrained in my memories that I’m not sure what to make of it – how much did it shape how I interpret everything that followed? It’s the backbone to my understanding of film. I can track my connection with it over time, the way it ebbed and flowed – it carries a certain oddness, a bit unorthodox for a Disney film. With each new viewing, I would either be taken in by its strange magic or underwhelmed with how it compared to my memories. It has never quite solidified.

It was a bit difficult to find the film again for that first revisit – to be honest, I’ve doubted your tale of my ceaseless observation since we didn’t seem to own a copy. I wanted to buy it but the dreaded Disney Vault kept it out of my grasp. Eventually, a friend of mine rented it and we sat on the floor of his bedroom to watch. The pure nostalgia overtook me – I remember being glad I was sitting further back from the television than my friend, leaving him unaware that I started crying at Mufasa’s death.

It’s strange, how easily that scene can choke me up even as a memory.

It’s only natural that, when I decided to attempt making long-form video essays, this was the first film I tackled. To be honest, I wish I did a better job – and it didn’t help I was at the time unaware of Youtube’s copyright bot and had to keep editing the video until it went through, leaving it messier than I intended. But hey – first attempts can be messy. The important thing is to keep powering through until everything comes together.

I really should make more…

This film might not have had the biggest impact on how I view cinema as an art form, but I’ve loved seeing how my perception of it evolves as my view of cinema changes. Is it too simplistic, or is there charm in that simplicity? Is the narrative structure a bit off, or is being a bit off what makes it stand out among the largely formulaic Disney canon?

Whatever new take I find, I always find comfort in knowing it’s there – a childhood blanket I now wear proudly as a cape.

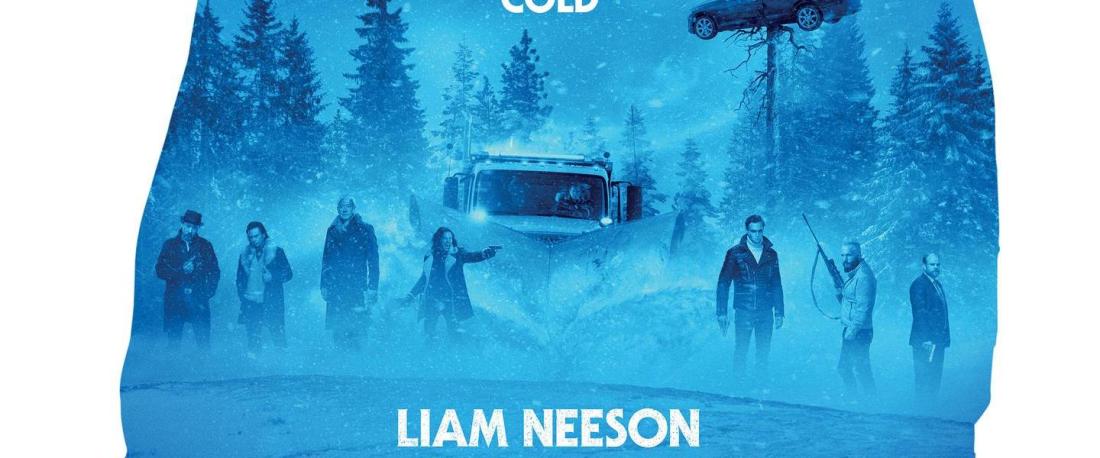

Review: Cold Pursuit (2019)

It would be nice to live in a world where a beat-by-beat remake of a relatively recent foreign film wasn’t seen as a viable pursuit – what a world it would be if people would simply go out and see the original. Though I can’t entirely blame them here, for I had never heard of the original until now (nor did I hear of this film until planning my weekly theater visit, but that’s another matter entirely).

Cold Pursuit follows Nelson Coxman (Liam Neeson) as he seeks out bloody revenge for the suspicious death of his son, soon finding himself caught up in a turf war between Trevor Calcote (Tom Bateman) and White Bull (Tom Jackson), two rival drug lords. Dozens of lackeys enter and exit the picture quicker than you can count, making small marks before violent deaths.

Cold Pursuit doesn’t feel extraneous purely due to its status as a remake – nearly every element is familiar. The film feels lifted straight from the 90s, echoing the darkly cynical humor of Tarantino and the Coen Brothers and their usual convoluted mess of characters. And while the snow drenched setting simply makes sense for a Norwegian film, the unfortunate fact is that moving this same narrative to America sets this movie up to be compared to the far better Fargo.

The element most miss while attempting to mimic Tarantino is that he carries a certain wit that justifies his violence; there’s a contrast between the mundanity of his conversations and the violence that soon follows. There’s no subtlety here – the villains are either total cartoons or bland stereotypes.

Trevor “Viking” Calcote is simply an awful villain, which makes a plot driven by revenge against him hard to invest in. His personality seems to consist of nothing but negative traits; he’s a controlling father, abusive, kills indiscriminately. There’s no attempt at humanization, laughable but not in the way most comedies are striving for. Tom Bateman goes completely over-the-top in the role – it feels as if the whole character was an attempt at some sort of meta-commentary on revenge flick villains, but he’s so laughable and surface-level that it doesn’t suggest anything but poor writing.

Liam Neeson does a passable job as Nels, but I never felt invested in his character arc. We know some facts of his life – recent “Citizen of the Year” recipient, snowplow driver, quiet life on the edge of a resort town. But his actual connections are underutilized – the son dies right at the beginning and his wife leaves soon after (Laura Dern serving in the wasted role). He’s the archetypal man with nothing to lose – and therefore nothing for us as an audience to care about.

The most intriguing element lacks the weight it needs. The seemingly endless henchmen get their own minor plots before being unceremoniously killed off, and if the movie just honed in more on a few, there could have been something there. Instead, everything is a cheap joke – a secret gay love affair here, a disgusting hotel habit there. Cold Pursuit has ideations of being an ensemble piece but every character is either flat or absurd.

Cold Pursuit wants to be a satire of the traditional Liam Neeson-style revenge flick, but its humor is too juvenile and its actual conflict too bare-bones to succeed. It’s a mess of violence without meaning – it almost seems to forget what the string of killing is about after a certain point. Revenge served cold does not imply burying it so far back in the freezer that even the audience forgets why it’s there.

2 Stars Out of 5

Review: The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part (2019)

The original Lego Movie was a surprise success, mixing together a popular but plot-less brand of toys and several pop culture references to somehow create a film about creativity among conformity. It worked at a level above its initial premise – no one quite expected it to be as effective as it turned out.

A problem with sequels is that they are sometimes simply more of the same, which can be especially problematic in a franchise that started with a film about rebelling against the status quo. The Lego Movie had to prove itself in a world where toy-based properties are rightfully questioned – it’s important to draw the line between an artistic production and glorified advertising. Now that the franchise has secured its place, The Second Part appears happy to fall into a now-familiar groove.

The premise is fairly straightforward, with a few necessary twists and turns – the world of the first movie is met with cataclysm after the daughter of the human family is allowed access to the Legos. Emmet, voiced by Chris Pratt, must rescue his kidnapped friends from alien invaders. During his journey, he meets Rex Dangervest (also voiced by Chris Pratt), who teaches Emmet a few new ways to interact with the world beyond simply creating. Lucy (Elizabeth Banks), one of the kidnapped citizens, tries to fend off the invaders while watching her friends fall easily under their spell – the obviously evil Queen Watevra Wa-Nabi (Tiffany Haddish) is delightfully charming in how blatant her manipulations are. Where the first film had order, the second carries chaos.

Though the film is a bit too familiar, the style holds up well enough to make this a worthwhile viewing. Scenes have a smooth flow and it playfully jumps in and out of various visual styles. There’s always something to catch the eye, though rarely the mind. There are plenty of decent jokes to go around, but nothing coheres to make an overall memorable experience – this is more a collection of fun moments than a centralized narrative force.

There’s an issue with the movie feeling too on-the-nose, from its humor to the narrative structure. The pop culture references tend toward the obvious, such as Rex Dangervest’s backstory simply being an amalgamation of every other Chris Pratt role. This particular joke seems to exist largely to draw our attention to the fact that Rex shares a voice with the protagonist – which, again, is a detail treated a little too obviously. The film is also dotted with live action shots that keep reestablishing that, yes, this whole affair is representative of a brother and sister fighting over toys. The messages are simplistic; siblings should learn to understand each other, and also sometimes things aren’t awesome.

Despite its poor handling of some big picture matters, The Lego Movie 2 succeeds at its individual moments. Rex offers up a good foil, his cartoonish edginess playing against Emmet’s infallible optimism. The best the film has to offer comes largely through Queen Watevra, a playfully meta character that is also connected to most of the musical numbers. The music throughout is incredibly fun, from the obvious villain song “Not Evil” to the aptly titled “Catchy Song” and the necessary “Everything’s Not Awesome.”

The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part is perhaps best compared to the over-produced pop songs it evokes – it’s designed to convey a certain light, accessible image, to be easily consumed by whoever comes in contact. These works don’t intrinsically lack value, but great art challenges to some capacity. The original film had the concept of originality to give it a necessary edge – the sequel doesn’t have a clear purpose beyond being a follow-up to a box office smash.

In the end, I kept finding myself comparing this film to another sequel starring Chris Pratt – much like the second Guardians of the Galaxy, this second Lego Movie simply feels like more of the same. The originals were both films I truly enjoyed and wanted to see more of, and I can be happy with what I ended up getting. But to make a great sequel, you can’t simply repeat but must also build upon the foundation – and of all franchises, shouldn’t Lego be aware of the need to build?

3 Stars Out of 5

You must be logged in to post a comment.