Developed by Obsidian Entertainment

While the Fallout series has been around for a while, the series went through a total transformation after changing publishers. The first two games were classic isometric WRPGs. As soon as Bethesda took over, they essentially changed it into The Elder Scrolls with a different setting. Fallout: New Vegas now feels like the most essential game in the series, combining the gameplay of the latter entries with the charm of the originals thanks to being developed by many involved in the older games.

New Vegas did not always sit atop that pedestal. Bethesda games are always busted, but New Vegas felt particularly unstable. When I first bought the game, I put it down after only an hour due to my character’s gun constantly bobbing up and down at random. It was the type of flaw which did not outright break the game but made the visual interface nauseating. It took picking up years later after tons of patches to see the true quality.

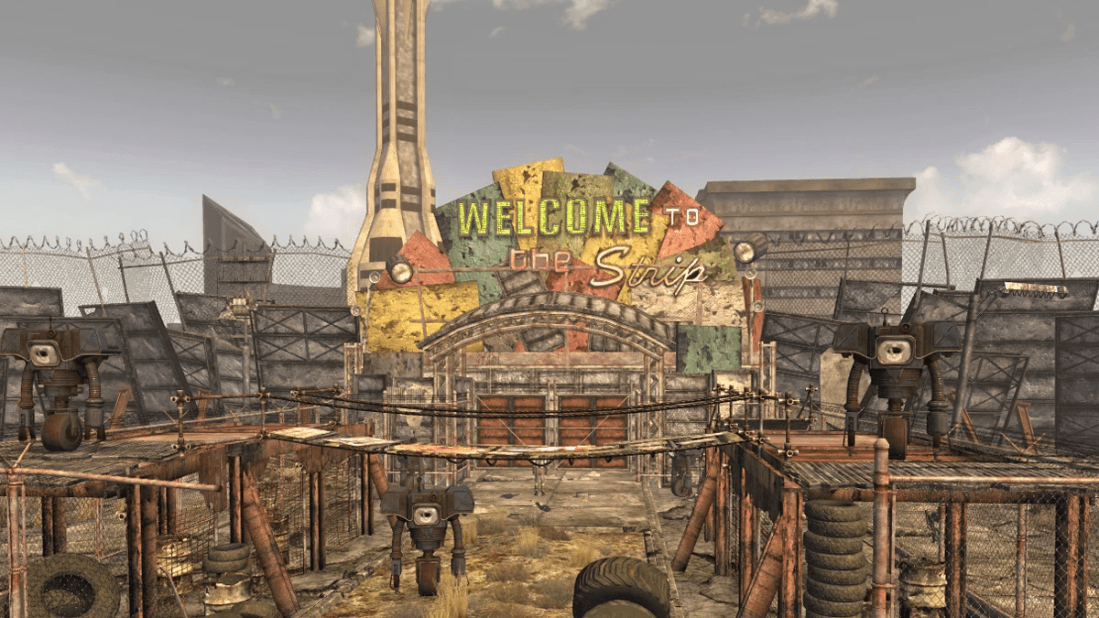

Fallout is at its best while being humorous. The numbered Bethesda entries have their fair share of comedy, but the settings can be a bit drab. Strolling through the National Mall in Fallout 3 is certainly a compelling experience, but the Las Vegas setting allows some brilliant nonsense.

What makes The Elder Scrolls work and thus Fallout by association is the massive amount of content to explore. Where most RPGs consist of caves and keeps, the retro-future setting of Fallout offers some truly unique locations. The series staple is the fallout vaults, which is how people survived into the present day. However, each and every vault was actually an experiment. Diving deeper and discovering their stories is always a joy. One feels lifted straight out of a Shirley Jackson social horror story while another has been overrun with fungus. The lore runs deep, always maintaining a darkly humorous atmosphere even as it descends into madness.

The quests are always a riot thanks to the many oddball factions. One gang consists of Elvis impersonators while one of the major factions vying for power has regressed into ancient Roman culture. The strip offers a dusty yet colorful environment, with each of the casinos having their own bonkers narrative. Despite being post-apocalyptic, so many of these areas feel alive.

I’ve always been a fan of how this series handles its nature as an RPG/FPS hybrid. The V.A.T.S. system is a stylized way to momentarily emphasize strategy over shooting. And while there are stat increases, a lot of the fun in levelling is choosing from the massive variety of perks. Some add new dialogue options, others make V.A.T.S. more versatile, while another reveals the entire map. There are so many ways to play this game, especially when considering the typical morality system which offers several ways of handling each quest. One of the most ingenious details is how dialogue options can change depending upon your build – including some special lines when your character is particularly unintelligent.

We put up with Bethesda’s glitches because the core experience tends to be so strong. There’s just so much to do here, and the game accommodates whatever playstyle you choose. With Obsidian’s brilliant writing, New Vegas is simply the best Fallout game.

You must be logged in to post a comment.