Developed by 2K Boston (Irrational Games) and 2K Australia

Would you kindly give me a moment to reflect before diving into BioShock itself?

And so, I finally reach the end of this project. I don’t think I realized what I was setting myself up to do when I established a goal of writing a minimum of 500 words for each game. With 100 games and 500 words being the equivalent of about 2 standard pages, I have essentially written something the size of a small novel, all for a project which was supposed to be a brief distraction as I took a break from editing my actual novel manuscript. Reaching this final moment is both relieving but also a bit of an anti-climax – is BioShock really my favorite video game?

The truth is, BioShock briefly dethroned Final Fantasy X as my favorite game in the time between its release and Persona 4 all those years ago – Persona 4 held my #1 spot until I played Life is Strange. While working on this list, I kept shifting these top six games around and nothing felt right sitting at the top. But the reason I wanted to write about all these experiences which have influenced me throughout my life was to reach a deeper understanding. One thing became perfectly clear – when comparing many of these games to outside experiences, BioShock came up the most, to the point I had to actively stop myself from mentioning it. One might think such universal applicability might be a sign of something generic, yet BioShock has always stood as its own entity. As I wrote while discussing BioShock Infinite, that sequel felt more like a lament that nothing could ever quite capture the magic of the original.

When we talk about great works of art, there is a constant struggle between giving credit to the innovators or the refinements. BioShock falls strictly in the latter category, doing nothing particularly new within the medium. But BioShock feels like a work which draws inspiration from every corner of classic game design to create something exceptional. The influence from other first-person shooters is obvious, but I also see shades of Resident Evil and several principal Nintendo design philosophies.

On the surface, BioShock takes the set-piece design revolutionized by Resident Evil 4 and Half-Life 2 and really perfects it. Like Half-Life 2, this is a first-person shooter which largely refuses to feature cutscenes. Outside of the opening and ending, there are only three I can remember, and they have obvious explanations for having to be presented that way, all while maintaining a first-person perspective and thus a sense of total seamlessness. Yet Half-Life 2 would largely fall back on locking Gordon in a room while other characters spoke to him. BioShock has a similar approach, but two changes make it more effective. First, the characters in BioShock usually get to the point. Second, the characters trapping Jack tend to literally be trapping him; the doors are locked because they don’t want you going forward. These moments are never tedious and tend to be full of tension, typically coming as a lead-in to a major confrontation.

As such, BioShock is one of the best examples of seamless narrative integration. But what if you want more? This is a world with some deep lore, and this is a game which rewards total exploration. While there is always an arrow pointed toward the next destination, the central areas are massive with several stray paths to explore. Rapture is littered with audio diaries, brief snippets from various residents as they reflect on the city. It’s up to the player to learn as much about the city as they desire.

The character design is surprisingly effective, especially for a game which pushed realism all the way back in 2007. Despite this, the enemies are designed to appear intentionally uncanny, helping them age better than BioShock’s contemporaries. Meanwhile, the Big Daddies and Little Sisters are two of the most striking creature designs in all of gaming. Nothing quite gets under my skin like a little girl laughing as she sees a dead body and saying that it’s dancing. Though the combat isn’t BioShock’s strongest point, fighting a Big Daddy is effective. There’s something about the animations of being knocked around that adds a visceral feeling which is lacking in most other FPS games that I have played.

The elements which truly push BioShock above so many other games is setting and atmosphere. Few worlds are as perfectly designed as Rapture, both as a conceptual place and through level design. The idea of Rapture is ingenious – what if a bunch of objectivists attempted to create their own twisted utopia on the ocean floor? As one particularly poignant audio diary puts it, someone has to clean the toilets. This is a city full of naïve opportunists too narcissistic to realize their position in the world was relative. With objectivism putting an emphasis on greedy upward mobility, this is a place where everyone wants to come out on top – but those already on top have the power to put everyone else down. And far beneath the ocean where the man in charge wants to keep the city a secret, everyone is trapped upon entry. Where most sci-fi and fantasy stories rely on a few familiar tropes, Rapture felt like a fresh idea.

The game design itself acknowledges this idea. There are health stations on every corner which seem capable of healing any damage, but of course they require payment. Even the security can be shut down as long as you have a few dollars – the city doesn’t care if you’re sneaking around where you shouldn’t be if you’re loaded. Even the bathroom stalls require payment.

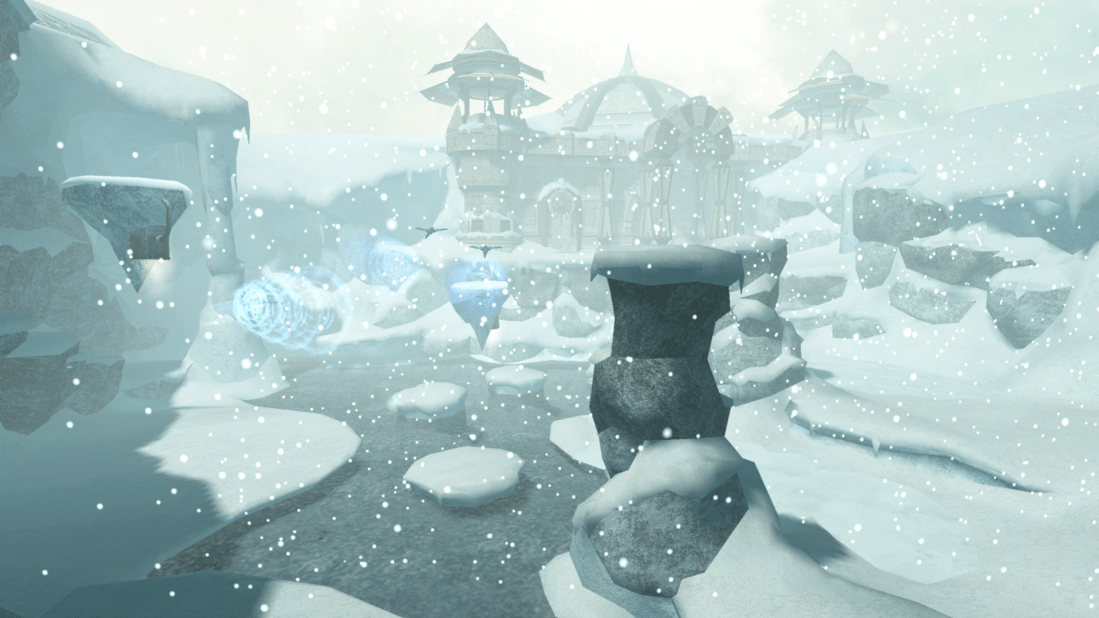

These levels all capture a specific brand of horror. The opening sequence shows a city in decay, suggesting the city will soon be flooded. Many of these stages revolve around a particular person going mad with power, and the Medical Pavilion is the perfect level to kick this off. Dr. Steinman has become obsessed with the idea of becoming the Picasso of surgery, which is exactly as horrifying as that sounds. Despite being surrounded by human beings, few games capture such an unsettling sense of isolation; the closest comparison is Metroid. And like Metroid Prime, this is a perfect example of an FPS where the emphasis is more on exploration than shooting.

The team behind BioShock went to great lengths to give each location its own feel. There’s a subtle color scheme that sets each of these stages apart, yet they all share the right features to feel like parts of the same city. Additionally, all of these stages are engaging. I used to be convinced there was a dip or two, but after replaying this game last week, they each serve a grand purpose.

While there are several great levels, Fort Frolic stands as one of the all-time best. While trying to jump from one passage to the next, Jack gets locked inside and is forced to do the bidding of Sander Cohen, a mad artist who has decided to hunt down his ‘disciples’ to create his masterpiece. It might be hard to imagine the artist quarter being the most terrifying, but the area is filled with his other great works; namely, dozens of dead people cast in plaster. Even worse, some of them turn out to be living…

Would you kindly accept my apology for needing to jump into spoilers for the next paragraph?

And then there’s the big bad himself, Andrew Ryan. Can you talk about BioShock without mentioning that famous scene? You will head into Ryan’s area expecting some explosive confrontation. Instead, the moment is stolen from you; as mentioned before, there are only a handful of cutscenes, yet they choose to put the most important moment in this form. Andrew Ryan explains the truth of this experience, which you might have started piecing together if you paid enough attention to the various audio logs. Jack is Andrew Ryan’s son who has been aged rapidly, thus explaining your ability to use the vita-chambers despite them only recognizing Ryan’s genetics. He then points out that Jack has been trained to follow any command which uses the phrase ‘would you kindly,’ revealing you have been used by the seemingly friendly Atlas from the very beginning, before forcing Jack to beat him to death with a golf club. All this while saying the famous line “A man chooses, a slave obeys.” BioShock and Portal made waves for outright acknowledging the idea that all video games must be programmed and are thus structured, no matter how many choices are offered – but then they push the idea of ‘breaking free,’ revealing the sense of freedom can work even while acknowledging these limits. This scene is perhaps the most important moment in video game storytelling, something which reshaped not just its own narrative but our perception of all others, and the fact it is pointedly a cutscene in a game which otherwise does without should not be overlooked.

It is difficult to call BioShock or any single video game the greatest ever. My own favorite game shifts constantly, and other games have held that title for a more consistent time. Yet it’s hard to overlook just how much this game does right. From the narrative to the atmosphere to the visual design to the sense of exploration, this is a game that does nearly everything right. Yet even this all-time great has one obvious flaw; as a first-person shooter, dozens of others have more engaging combat. My love of BioShock is actually a bit of an oddity – I have never been the biggest fan of this genre. But like Psychonauts or Metroid Prime, BioShock works wonders when viewed more as an interactive adventure. Few experiences have hit me like exploring this underwater testament to humanity’s greed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.