Developed by Square

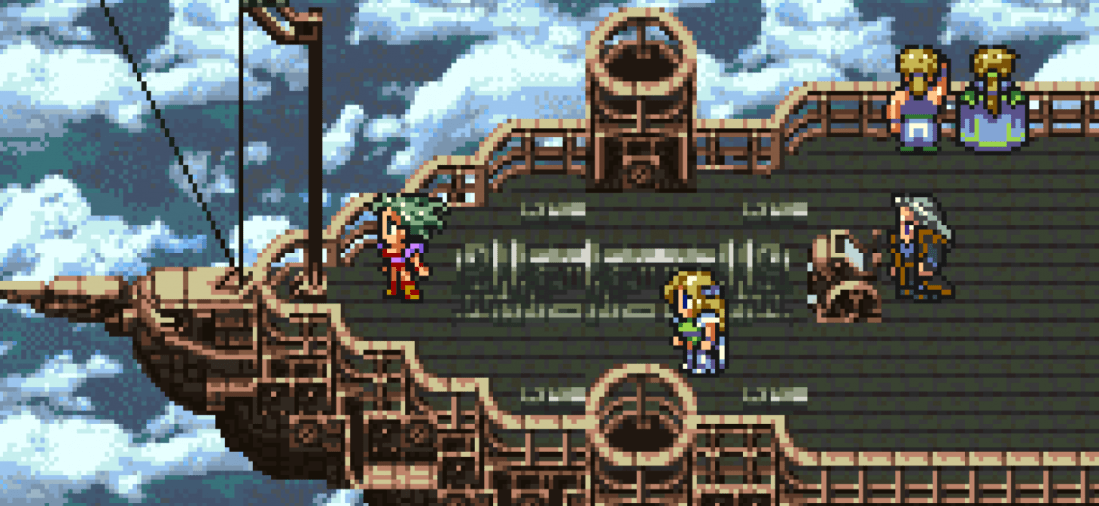

While IV and V are truly great in their own right, VI is when the Final Fantasy series started churning out downright masterpieces year after year. VI builds upon IV’s narrative foundation (V still stands as a distinct entry), telling the story of a bunch of plucky adventurers as they fight to save their world. Where IV was always centralized around Cecil and most of its revolving cast consisted of temporary characters, VI does away with a protagonist entirely.

Some will argue that Terra or Celes are the ‘true’ main character. This doesn’t really matter. Significant is the fact that this structure allows the game to constantly split the party while never relegating any party member to a minor role. This culminates in a final dungeon where the player must split their 14 party members into three teams of four. Many JRPGs have giant casts, but few utilize them all in such a meaningful way.

This split structure also helps highlight each member of this colorful cast. While the quality isn’t exactly consistent, characters like the Figaro brothers, Terra, Celes, Shadow, and Locke all rank among the best in the series. Then there is the first unforgettable villain in the series, dancing mad court mage Kefka Palazzo. His colorful outfit hides a ruthless sadist who only wants to see the world destroyed. The game doesn’t even treat him as a serious threat initially. His cackling soundbite is spine-tingling, and he’s one of the few convincing displays of destructive nihilism. There’s no cheap stab at creating sympathy – Kefka is a living embodiment of evil, plain and simple. The heroes absolutely have to stop him.

And what makes Final Fantasy VI so effective is that they don’t. Not initially. The game is divided into two distinct halves. The opening is rather straightforward beyond its branching paths, but the second half turns closer to an open world experience as Celes finds herself in a shattered world. All of the heroes have been split up, and the team must reunite to have a chance at getting their revenge on Kefka. This atmospheric shift was key in establishing FF6 as having one of the first truly great video game narratives, and it also gave the player a chance to have their own sense of control as they sought out the remaining heroes.

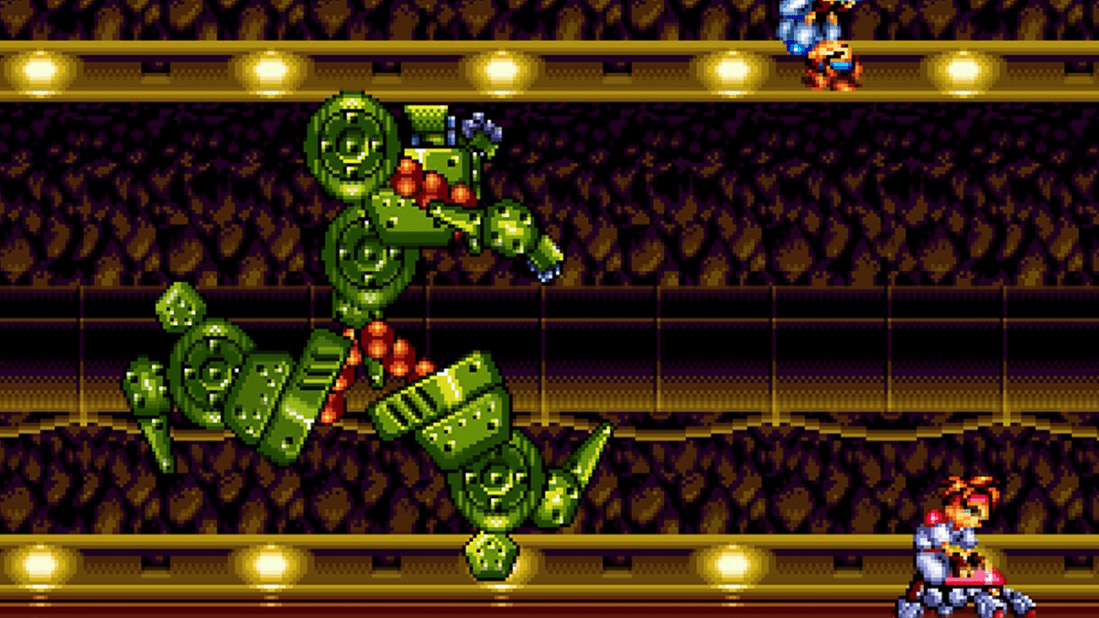

With its fourteen party members, FF6 stands out by giving each of them a clearly defined function through a special command. Sabin pulls off awesome physical feats which must be input like a traditional fighting game. Gau imitates enemies through his rage ability. Edgar utilizes special tools with a variety of effects. Each and every character fills a niche. Meanwhile, the esper system gives the player a bit of control over how the characters level and gain magic.

Most modern JRPGs have Final Fantasy IV to thank for establishing solid narratives in traditional video games. Final Fantasy VI refined these elements. From a strong cast to a surprisingly dark narrative to a large world to a phenomenal soundtrack by Nobuo Uematsu, this is everything you could ever want from a Final Fantasy experience, years before VII finally set the world on fire.

You must be logged in to post a comment.