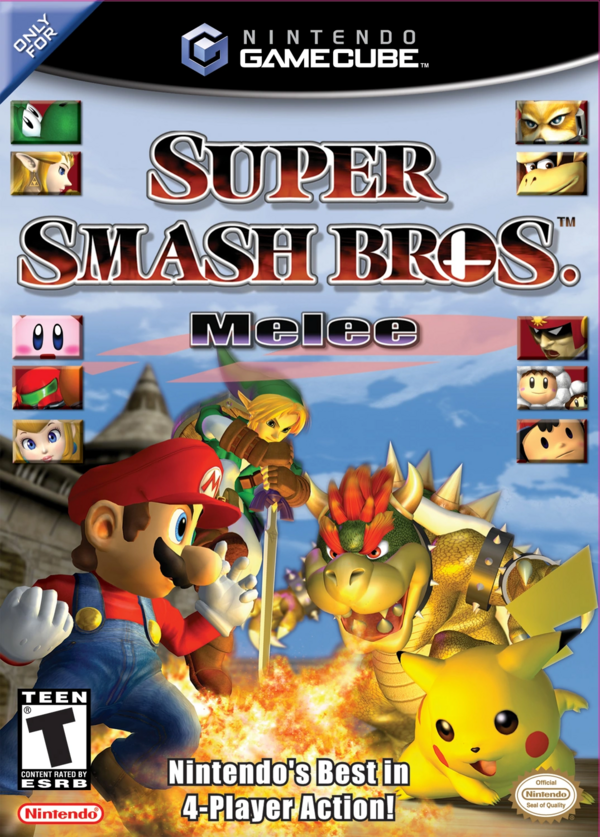

Developed by HAL Laboratory

As much as the roster keeps increasing, there’s something about Super Smash Bros. Melee that hasn’t been outright replaced by Ultimate like its following two sequels. Part of this is certainly nostalgia, but there’s something to be said about a tighter roster and Melee’s fluid motion.

When I finally got a Nintendo Gamecube, the only consoles I had owned before were a Sega Genesis, a Game Boy Color, a PlayStation 2, and a Game Boy Advance. Thus, my experience with Nintendo was largely limited to the Pokemon series and Super Mario Bros. Deluxe; there were certainly others I could have picked up with the handheld systems, but I had no one to push me in the right direction. Since I wanted this system to be able to play with more friends, my first games were Mario Kart: Double Dash and Super Smash Bros. Melee.

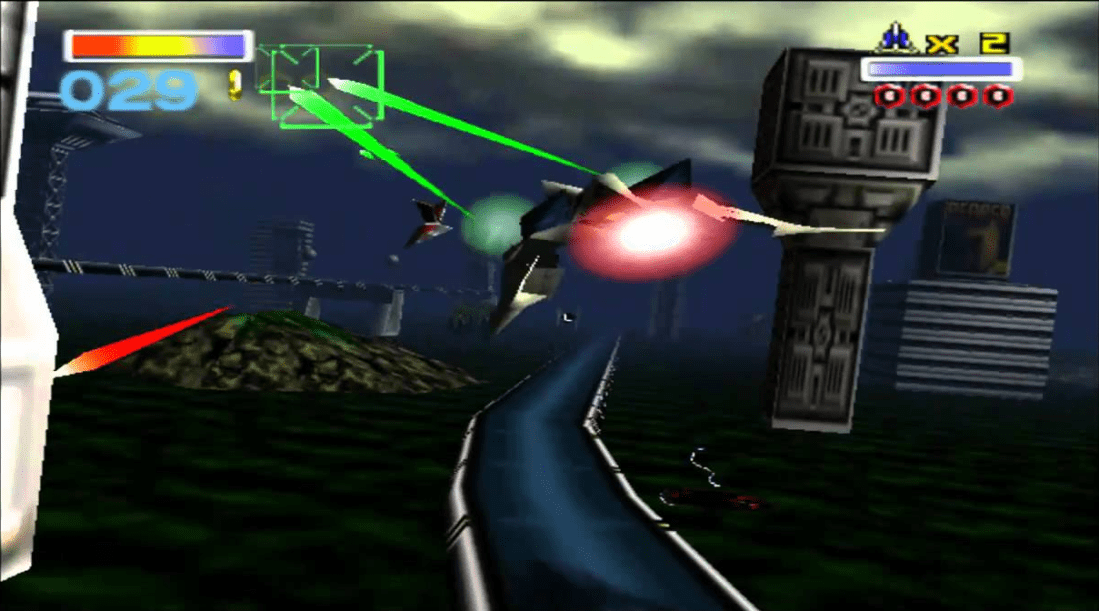

Beyond its (now small) roster, this game was loaded with Nintendo content. I could get lost in the trophies and their descriptions. With friends as clueless as I was beyond the colorful platformers of the time, this was my first real gateway into gaming at large. Melee guided me to Metroid Prime and F-Zero GX. Getting lost in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker in turn led me to discover GameFAQs on the final day of its third character battle, where Link himself narrowly defeated some obscure character named Cloud Strife. While my interest in those contests turned into my biggest gateway, it all started with Super Smash Bros. Melee’s celebration of its own history.

There are few games I have invested more hours in than Super Smash Bros. Melee; even after the release of Brawl, most of my friends preferred the feeling of Melee (which was then compounded by my Brawl disc inexplicably not working for a year before suddenly working again). Mario Kart was fine enough, Mario Party fun in its own stupid way, but Melee dominated all up until the Rock Band craze (which itself largely signaled the end of video games in my social life, replaced by board games as I entered college). My preference for games leans toward the single player experience, but Melee has always had its own special pedestal.

Part of the appeal over later sequels is the simplicity. Roster additions starting with Brawl felt more and more specialized (which is not bad, considering I place Melee and Ultimate on a near equal level). With only 26 characters and a few of those being clones, it was easier to learn how to fight with and against each potential style. In the end, if you mainly play with a few friends and those friends tend to stick to a handful of fighters at best, a larger roster does not change too much. I always preferred the frenetic feel of Melee, even as a casual player. Something about falling faster made every second more urgent.

So, yes, a large part of this inclusion plays into my nostalgia; but while compiling a work on the hundred games which influenced me most, it would be wrong to exclude something which dominated nearly a decade of my life. The simple fact that Melee vs. Ultimate is an argument at all is a testament to how much Nintendo got right all the way back in 2001. Even with the series pushing 80 characters, it is all based around Melee’s core design.

You must be logged in to post a comment.